Behavioural economics intends to model humans in a more realistic way and attempts to make economics a more relevant and powerful science of human decision making and behavior by integrating insights from Psychology, Sociology, Social Psychology and Anthropology into economics. Experimental economics adapts methods developed in the natural sciences to study economic behavior. Experiments are valuable in testing to what extent the integration of insights from other disciplines into economics. Experimental economics is about real people, making real choices for a real money. Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel Prize winner in 2002, was a pioneer on the utilization of this innovative science. Nowadays, Richar H. Thaler is the main figure since he has been awarded the Nobel Prize in 2017 for his work on behavioral economics.

Irrationality and cognitive biases

Humans make about 35,000 remotely conscious decisions a day and unsurprisingly, many decisions lead to undesirable outcomes. Humans, organizations and societies are capacity-limited. Humans are expected to make optimal decisions, however, people are influenced by feelings, emotions, etc., they are cognitively limited. A cognitive bias is a systematic (non-random) error in thinking, it is a systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment. The study of heuristics and biases are core elements of behavioral economics. These mistakes are not the consequence of brain failures. On the contrary: as far as it is impossible to use all available information people make decisions using heuristics. These heuristics provide shortcuts in order to save time and effort to the brain. Thus, the application of heuristics is often associated with cognitive biases.

Bounded rationality

Bounded rationality is a human decision-making process in which we attempt to satisfice, rather than optimize. In other words, we seek a decision that will be good enough, rather than the best possible decision.

Example: Imagine you won a contest, and you are given two options for your reward. Either you can receive $100 today, or you can wait one month and receive $110. The perfect rational individual would choose to wait one month to receive the larger sum of money, but most people are likely to be satisfied with receiving $100 immediately.

Anchoring bias

Tendency to pay too much attention to the first piece of information we receive or to a previous reference. This can skew our judgment, and prevent us from updating our plans or predictions as much as we should.

Example: in an auction, it is not logical to make an offer below the initial bid, even if this one is far above the real value of the product.

Framing

The decisions are influenced by the way information is presented. Equivalent information can be more or less attractive depending on what features are highlighted.

Example: although the sentences “90 patients have survived” and “10 patients have died” in a month in a hospital include the same information, the reputation of that hospital may be interpreted in a slightly different way.

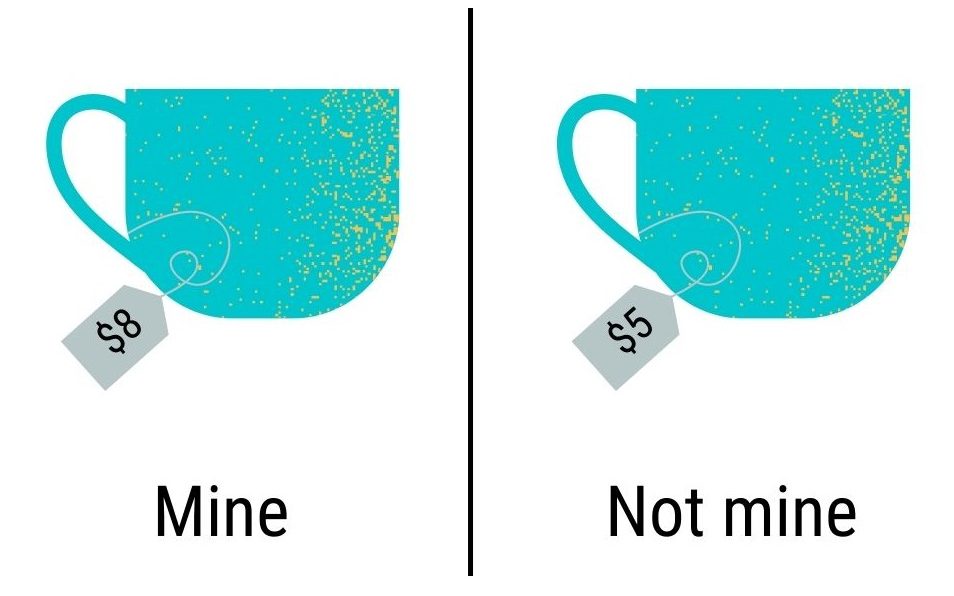

Endowment effect

The endowment effect describes how people tend to value items that they own more highly than they would if they did not belong to them. This means that sellers often try to charge more for an item than it would cost elsewhere.

Example: Let’s say a few months ago, you bought a concert ticket for $100. You just found out that you won’t be able to make it to the concert after all, so you decide to resell your ticket. You price the ticket at $150, because just selling it at market value would feel like you were losing out.

Confirmation bias

People usually consider the information that supports their own hypothesis only and discard the one that goes against it.

Example: Presented with someone else’s argument, we’re quite adept at spotting the weaknesses. Almost invariably, the positions we’re blind about our own.

Extrinsic incentive bias

The extrinsic incentive bias relates to the tendency to attribute other people’s motives to extrinsic incentives, such as job security or high wages, rather than intrinsic ones, such as learning new things or building a new skill.

Example: People usually overestimate the value employees place on external rewards such as money, and underestimate the value they place on internal rewards.

Overconfidence

Overconfidence bias refers to the tendency of people to have excessive confidence in their abilities, knowledge, and ideas. This can impact their decision-making.

Example: Starting a business is risky and costly, and more new businesses fail than succeed. Yet part of the entrepreneurial mindset is the confidence that you will succeed where others haven’t. While this borders on overconfidence, it helps weed out people who lack the resolve needed to be an entrepreneur.

Hyperbolic discounting

Hyperbolic discounting is our inclination to choose immediate rewards over rewards that come later in the future, even when these immediate rewards are smaller.

Example: Have you ever noticed that some websites offer payment plans that don’t make financial sense? Here’s the type of thing they offer:Buy 1 month: $9.99 or Buy 1 year: $39.99 . If one year costs $39.99, then one month at the yearly rate is only $3.33. Why would anyone pay $9.99 for one month? Hyperbolic discounting, that’s why. The user wants to pay less now. They consider the issue from a hyperbolic discounting perspective, not a true value perspective.

Mental accounting

Mental accounting explains how we tend to assign subjective value to our money, usually in ways that violate basic economic principles. Although money has consistent, objective value, the way we go about spending it is often subject to different rules, depending on how we earned the money, how we intend to use it, and how it makes us feel.

Example: When we buy something that we don’t intend to use right away, mental accounting can make that expense feel smaller than it would otherwise. This is because we tend to think about these purchases as “investments,” rather than normal spending. On top of that, whenever we eventually do consume the product we bought in advance, we feel like it’s “free” because we paid for it so long ago.

Heuristics

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that can facilitate problem-solving and probability judgments. These strategies are generalizations, or rules-of-thumb, reduce cognitive load, and can be effective for making immediate judgments, however, they often result in irrational or inaccurate conclusions.

Example: The scarcity heuristic, which refers to how we value items more when they are scarce, can be used to the advantage of businesses looking to increase sales. Research has shown that advertising objects as “limited quantity” increases competitiveness among consumers and increases their intentions to buy the item.

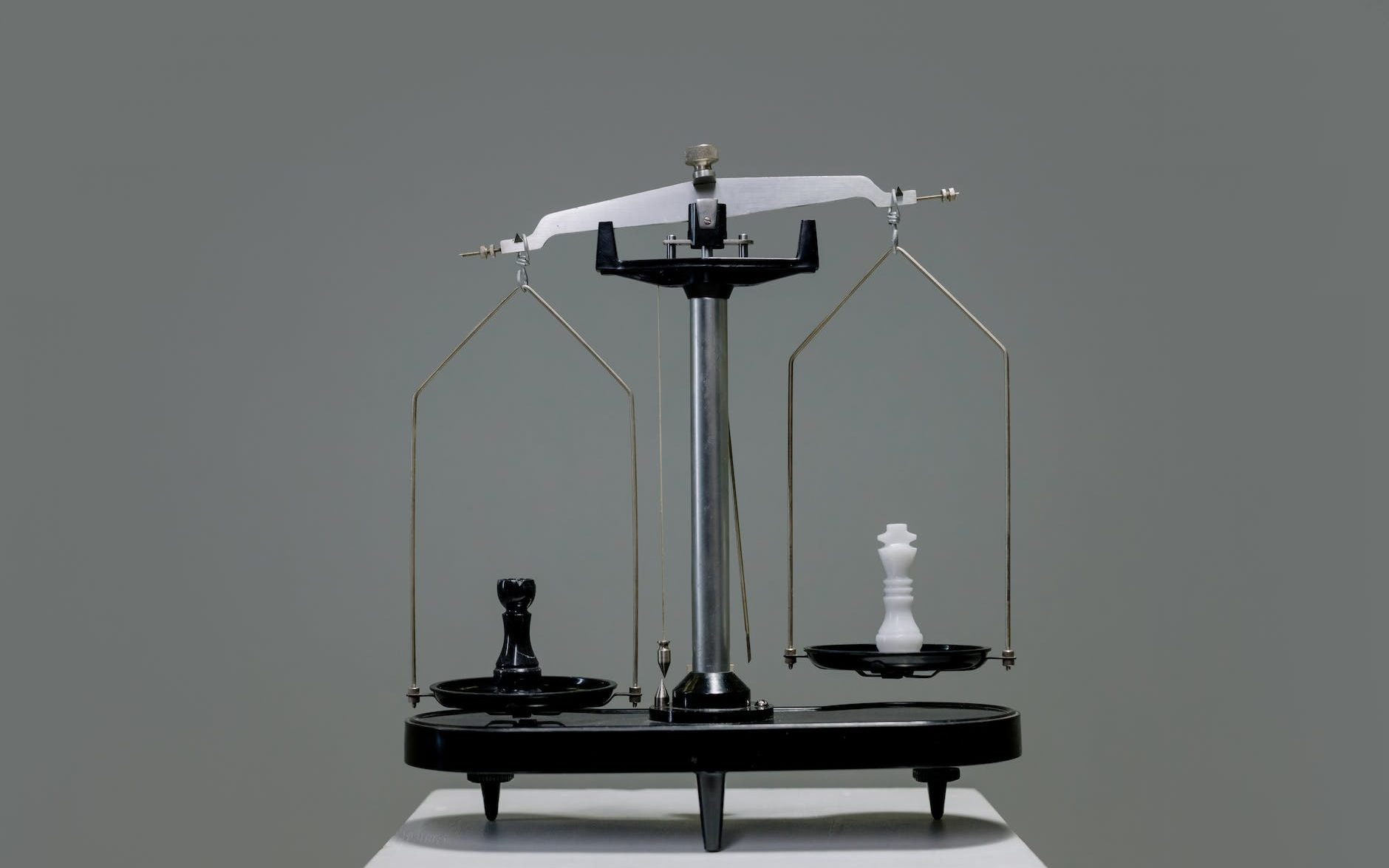

Loss aversion

Loss aversion is a cognitive bias that describes why loss felt from money, or any other valuable object, can feel worse than gaining that same thing.

Example: The reserach found that the losses are twice as powerful compared to their equivalent gains. For example, the pain of losing $50 dollars is far greater than the joy of finding $50.

Bandwagon effect

The Bandwagon effect refers to our habit of adopting certain behaviors or beliefs because many other people do the same.

Example: The bandwagon effect arises when people’s preference for a commodity increases as the number of people buying it increases. Consumers may choose their product based on others’ preferences believing that it is the superior product. This selection choice can be a result of directly observing the purchase choice of others or by observing the scarcity of a product compared to its competition as a result of the choice previous consumers have made.